From the Beijing Winter Olympics to Xi’s likely third term, these are five things to look out for in China in 2022. Will President Xi Jinping be able to gain a third term, as many predict, and will this result in even tighter control? And how far is a resurrected Xi ready to go?

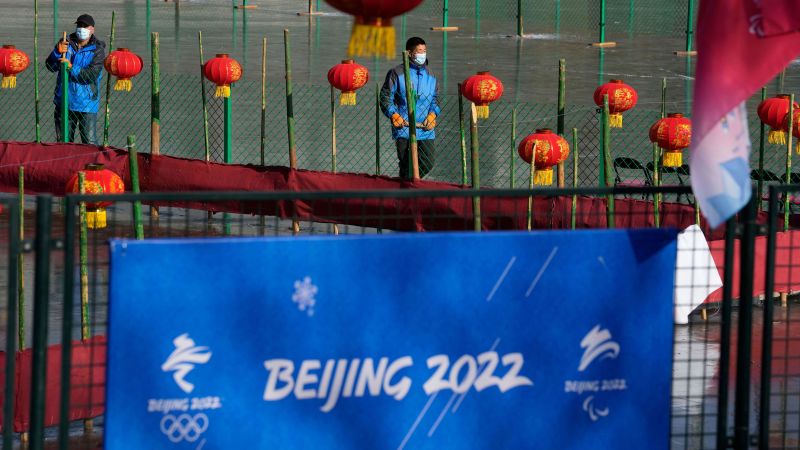

What about China’s position on the global stage? Will Beijing’s relations with the United States deteriorate further? Will China stay isolated from the rest of the world as the coronavirus epidemic enters its third year? The spotlight will be on Beijing, the first city to host both the Summer and Winter Olympics.

The difference between the two Games, though, is remarkable.

Whereas the 2008 Summer Olympics were widely regarded as China’s “coming out party” on the international stage (complete with the official theme song, “Beijing Welcomes You”), the 2022 Winter Games will be held within a tightly sealed Covid-safe “bubble,” isolating participants and attendees from the rest of the Chinese population.

As the Summer Olympics in Tokyo demonstrated, organising a major international athletic event amid a pandemic is no simple undertaking. And it is all the more difficult for China because of its commitment to eliminate the virus within its borders.

Chinese officials will be on the lookout for more than only the coronavirus. Athletes and other participants will be rigorously scrutinised in order to avoid any potentially humiliating acts of protest against Beijing.

Activists have long advocated for the Games to be boycotted in protest of China’s human rights violations in Xinjiang and Tibet, as well as its political repression on Hong Kong. The recent silence of Chinese tennis player Peng Shuai’s sexual assault charges against a former senior leader by Beijing has heightened such calls.

The United States and other allies have already declared a diplomatic boycott of the Games. And, while athletes from those nations will still be permitted to compete, there is a chance, however remote, that some will feel compelled to speak out.

Following a series of coronavirus outbreaks and expensive lockdowns, concerns about China’s ambitious zero-Covid plan remain unanswered.

For the time being, there is little indication that Beijing is inclined to shift course. In fact, attempts to eradicate the virus have only increased in the run-up to the Beijing Winter Olympics.

13 million inhabitants of Xi’an, a historic city in northwest China, have entered their ninth day of house confinement as officials seek to manage the country’s greatest community epidemic since Wuhan, the pandemic’s initial hub.

Local officials, on the other hand, were unprepared for the harsh regulations they enforced. Over the last week, Chinese social media has been overwhelmed with pleas for assistance from Xi’an residents who are experiencing food and other vital supply shortages as stores close and private vehicles are prohibited off the roadways. Access to medical services was also hampered, as one university student described being turned down by six institutions for treatment of a fever.

Thousands of people said goodbye to 2021 on Thursday by posting notes on the dormant Weibo account of Li Wenliang, the Wuhan doctor who was jailed by authorities for raising the alarm about the coronavirus before succumbing to the sickness.

“Hi Doctor Li, it’s been two years, and those overseas are still unable to return home, and those at home may suffer food shortages,” one commenter remarked.

Li discovered the virus on December 30, 2019, and immediately informed colleagues. People have been posting on the whistleblower’s account on a regular basis since his death.

“Two years ago, I didn’t take this minor bit of news seriously and even dismissed it as an overreaction.” I had no clue it would come out the way it has now. “I hope you’re resting well in Heaven and that we’ll get over this someday.”

Throughout 2021, some believed that China might relax its zero-tolerance policy after the Winter Olympics, while others were more pessimistic, pointing to an important Communist Party conference in the fall as a possible impediment for the government to risk the virus spreading.

All indications point to Xi gaining an unprecedented third term in power at the ruling Communist Party’s 20th National Congress this fall in Beijing.

Xi, China’s most powerful leader in decades, has already eliminated presidential term limits and written his namesake political theory into the country’s constitution. In 2021, he went a step further, with the passage of a major resolution that elevated him to the same pedestal as modern China’s founding father Mao Zedong and reforming leader Deng Xiaoping — assuring Xi’s unrivalled control inside the authoritarian, one-party state.

Few Chinese leaders have loomed so big over the lives of 1.4 billion Chinese people since Mao and Deng.

The party has increased its grip on all parts of life under Xi, from art and culture to schools and enterprises. It has repressed an increasing number of critical voices in public, assassinated a rising number of China’s top stars, and expanded its reach even farther into citizens’ private lives.

Meanwhile, Xi has fought an ideological fight against what he terms the “infiltration” of Western principles including as democracy, press freedom, and judicial independence, and has stoked a strain of narrow-minded nationalism that views the West with distrust and outright contempt.

While Xi’s vision is at odds with those who grew up believing their country would become more open and connected to the rest of the world – as it had in the decades following Deng’s “reform and opening up” policy – in the eyes of Xi and his supporters, China has never been closer to its dream of “national rejuvenation,” having amassed unprecedented military strength and economic might.

China is dealing with a number of issues that might have a significant impact on growth in 2022, ranging from periodic Covid-19 outbreaks to supply chain problems and a protracted real estate crisis.

The country is still predicted to develop significantly in 2021, with many experts predicting 7.8 percent growth. However, major banks have reduced their growth predictions for 2022 to between 4.9 percent and 5.5 percent. That would be the second-slowest growth rate since 1990.

The goal to keep the nation operating stably ahead of his widely anticipated historic third term is almost probably at the forefront of Xi’s thoughts. He’s already demonstrated a willingness to focus on internal matters rather than huge international ambitions: Xi hasn’t left the country since the epidemic began, and his administration has carried forward with its extreme “Covid-zero” policy, which much of the world has abandoned.

Analysts say Xi must examine the outside world to some extent since China still relies on foreign financial centres for investment, technology, and commerce.

During the early stages of the epidemic, Beijing intended to use the global health catastrophe to improve its image. It supplied face masks and other medical supplies to needy nations and promised to make Chinese vaccines a worldwide public benefit.

While China’s success in quickly containing the virus has garnered widespread support at home, its international reputation has suffered as a result of its initial mishandling of the Wuhan outbreak, the disinformation spread by its diplomats and propagandists abroad, its continued crackdowns on Xinjiang, Tibet, and Hong Kong, and its increasingly assertive stance toward its neighbours.

It hasn’t helped his public image either. In most of the locations polled, trust in Xi is likewise approaching historic lows. Majorities in all but one of the 17 nations polled (Singapore being the exception) say they have little or no trust in him, with half or more in Australia, France, Sweden, and Canada saying they have none at all.

China’s ties with the United States worsened significantly in 2021, as tensions with Taiwan grew. To offset China’s ascent, President Joe Biden has sought tighter connections with like-minded countries in Europe and the Indo-Pacific region. And such attempts are only expected to intensify in the next year.