Of course this was going to happen. It’s only a wonder it hasn’t happened sooner.

College football is a sport where more than three years after players were finally allowed to monetize their name, image and likeness, there are still no clear guidelines governing the marketplace.

There is no governing body with real teeth to enforce what little rules there are for either side of a contract, and if anyone tries, an offended party can hire a lawyer, go to court and add another chapter to the NCAA’s long line of failures in convincing a judge that its business model is fair.

Last week, UNLV starting quarterback Matthew Sluka posted that he planned to leave the program after “representations” made to him “were not upheld.”

— Matthew Sluka (@MatthewSluka) September 25, 2024

His father, Bob Sluka, told The Athletic there was essentially a verbal agreement from January to pay Matthew $100,000 for his final season of college football. Instead, he’d been given only $3,000 for moving expenses, and despite efforts to pursue what was owed, Bob Sluka said, had yet to be paid anything further from UNLV’s collective since graduating from Holy Cross this summer and showing up in Las Vegas.

However, Blueprint Sports CEO Rob Sine said in dealing with Sluka’s representation beginning Aug. 29, there was no mention of any money owed, and UNLV’s collective denied a deal existed and UNLV said it had honored all “agreed-upon scholarships” for Sluka.

GO DEEPER

An NIL disagreement led to an early split at UNLV. Will this set a precedent?

The No. 25 Rebels, who host Syracuse on Friday and are near the front of the line for a Group of 5 bid to the College Football Playoff, are moving on.

Unfortunately, plenty of pitfalls exist in a quickly changing, largely lawless system that is evolving from an exploitive Stone Age into a sport that treats players — its most valuable asset — equitably.

Eventually, I believe college football will reach a place with something resembling player contracts, the ultimate fix for situations like these, produced by schools and with mostly standard language. Eventually, college football will share some of the billions of dollars in television revenue with the players, making sure that schools have at least some money to give players.

But this doesn’t have to be you or your program. There are lessons to be learned from this unsightly saga.

1. Don’t do anything unless everything is in writing.

Both sides agree there was never a written agreement. But the Slukas say a verbal agreement with Matthew’s agent and UNLV offensive coordinator Brennan Marion was made in January, months before Sluka made the move from Massachusetts to Nevada.

There are barely any norms. And what norms there are vary from collective to collective and school to school.

“A lot of the conversations I had, the head coaches would bring up money directly,” a player who navigated the transfer portal told The Athletic this offseason for a survey about the inner workings of NIL. “They would talk about the numbers that they give to players at my position based on how much value they deem based on the level of recruit that you are and how much playing time you’ll have.”

GO DEEPER

College football portal confidential: How tampering, NIL deals and portal chaos happen

No player is more valuable than the starting quarterback, though Sluka still had to win the job over Campbell transfer Hajj-Malik Williams, who led the Rebels to a win last week over Fresno State.

In February, a federal judge in Tennessee blocked the NCAA from enforcing what laws the organization did have governing NIL. Sluka arrived at UNLV in June and began classes on Aug. 26. In all that time and through three games, he didn’t get it in writing. But he wanted to be a team player, so he kept playing.

And eventually, Skuka realized he went to Vegas and rolled snake eyes.

Fair or not, his decision to leave a team chasing a Playoff bid a month into the season will cost him his reputation in the eyes of many.

Nobody should make major changes in their life based on financial arrangements without a written agreement enforceable by lawyers.

GO DEEPER

Welcome to Las Vegas … the epicenter of college football chaos?

2. Get the right representation.

There is no agent certification process in college football beyond what some states require to do business as an agent, and the quality of agent varies widely.

Sluka’s agent, Marcus Cromartie, splits his time between college and NFL clients, but he was reportedly not certified to operate in the state of Nevada, which gave some around UNLV pause in dealing with him.

“That was very odd to me,” another agent told The Athletic.

It’s unclear why an agent would take a promise by an offensive coordinator as binding. But it was never made official.

“We tried everything. We’d take payments. Anything. And they just kept deferring it and deferring it, and to this day, we do not know why,” Bob Sluka, Matthew Sluka’s father, told The Athletic last week.

Emails obtained by The Athletic show Cromartie never broached the $100,000 in his brief communications with UNLV’s collective.

Former Florida signee Jaden Rashada did get his contract in writing, but his representation also allowed Florida’s collective to get in writing that it could terminate the contract at any time. They shorted him more than $13 million. Rashada sued the collective and Florida head coach Billy Napier this May.

3. Coaches: Know your collective.

Coaches can endorse their third-party collectives and have conversations with them, both things that were initially banned when NIL was instituted in 2021 and collectives sprouted from the NCAA rule change.

The most effective schools have great communication between the two, and the chief reason for that is budgeting. Coaches and staffers need to know how much money is on hand for a collective or how much could reasonably be raised for a transfer prospect or a high school recruit.

Bob Sluka said his son’s agent was hoping to speak with Hunkie Cooper, a UNLV support staffer, after the team’s win at Kansas on Sept. 13, saying he recalled Cromartie saying “that’s the guy who’s avoiding us right now about the money.”

A later conversation produced an offer from Cooper for $3,000 a month for the next four months, telling the Slukas to take it or leave it.

In the world of collectives, $100,000 is not a lot of money for a quarterback and especially not for a starting quarterback of a Top 25 team hunting a Playoff spot. For UNLV to be able to offer only $3,000 a month for the rest of the season points to a glaring disconnect between the coaches’ vision for their roster and the means of the collective.

Few, if any, coaches are going to make a promise they have no intention of delivering. Word travels fast, and there’s no quicker route to eroding trust with your current roster and future prospects. A member of the coaching staff discussing financial numbers for a player is against NCAA rules, though according to agents interviewed by The Athletic, it happens all the time.

“I prefer to deal with the coaches because they’re so out of their element. They’re like, ‘We can get it done.’ There’s an ego thing — you want to get it done for your position group and your school, show you’ve got money,” one agent told The Athletic this offseason in the NIL survey.

Whether or not Marion made what he believed to be a firm verbal offer, Sluka believed it was and felt strongly enough to leave the program over it. Negotiating the finer points of an offer with a coach is rare, an agent told The Athletic this week, but somewhere between the recruiting process and fulfillment of an NIL offer, the Slukas and Marion weren’t on the same page.

4. Honesty is the best policy.

If there was no money, UNLV would have been well-served to explain that to its starting quarterback.

I spoke with people around UNLV’s program this offseason who were complaining that a lack of NIL support was a big reason why the Rebels were unable to keep starting quarterback Jayden Maiava, who committed to Georgia before flipping to USC, where he’s now Miller Moss’ backup instead of chasing a Playoff bid with a team he helped lead to nine wins a season ago. He threw for more than 3,000 yards and ran for almost 300 more in Marion’s innovative Go-Go offense.

Maiava left for much more than $100,000, a person briefed on the situation told The Athletic, but that lack of support is what put UNLV on the market for a transfer quarterback in the first place.

And this situation could hurt the program and hurt both Marion and head coach Barry Odom on the recruiting trail, despite the program’s denials about what unfolded or Odom’s level of involvement.

UNLV said in a statement it interpreted Sluka’s “demands as a violation of the NCAA pay-for-play rules, as well as Nevada state law.”

That might technically be true, but those NCAA rules were already defeated in a Tennessee court in February, and the way college football is operating in 2024 is that players expect to be paid, especially if they believe they had reached a deal.

Blueprint Sports, which runs UNLV’s collective, released a statement that there were “no formal NIL offers” made to Sluka and that the collective “did not finalize or agree to any NIL offers.”

That’s true. And it’s going to hold up in court and prevent Sluka from pursuing any legal action.

But it doesn’t tackle the real issue, which is that he says he was promised money from a coach, who had had no agency to deliver it, and it wasn’t there to begin with.

5. Think through all your options.

When Sluka hit “post” on his announcement last week, he chose the nuclear option. He is moving home to Long Island, his father said; his time with the program is done.

Sluka leaving the team opened the door to him being called a quitter. There’s a portion of the population who will never see it any other way, even if they would also quit their job if they believed they had been promised $100,000 and were paid $3,000.

But he had options. Might I suggest a more creative one?

Given how fruitless the Slukas say their efforts had been to resolve the issue privately, Sluka could have publicly explained his situation, either by posting a video or statement on X. Sluka could have publicly professed his willingness to be a team player, kept working and kept his coveted spot as the starting quarterback for a Playoff contender.

Barely 12 hours after Sluka’s post announcing his exit, Circa Sports CEO Derek Stevens reportedly offered to pay him $100,000 to resolve the dispute but was told by UNLV the relationship was already too far gone.

By going public only after the relationship had been severed, he didn’t get any of the money he believes he was promised and in the eyes of many lost the public relations battle.

That’s a tough 1-2 punch, and it didn’t have to go down that way. Whatever happens between now and next season, it’s hard to imagine Sluka will end up in a better on-field situation.

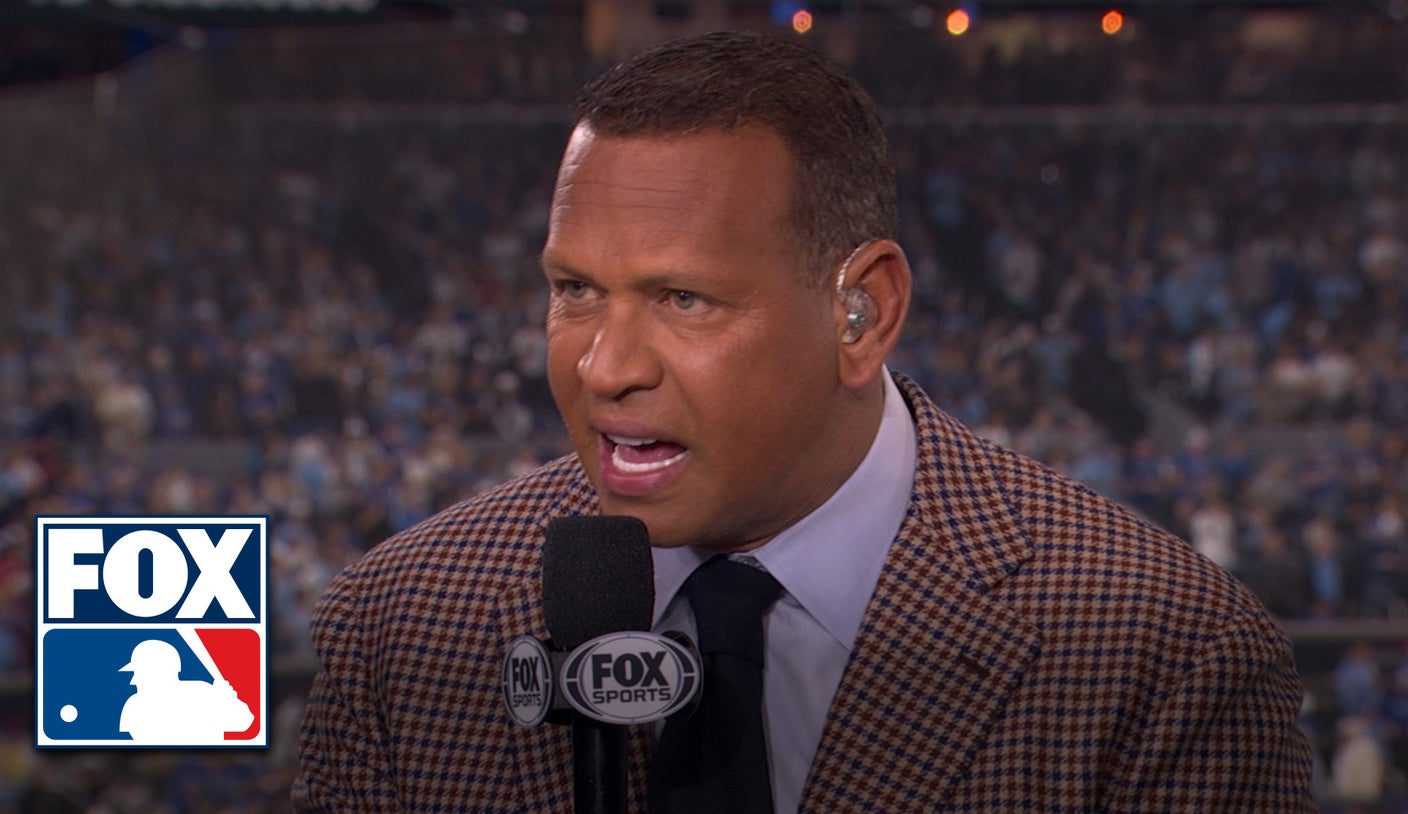

(Photo of Matthew Sluka:Kyle Rivas / Getty Images)